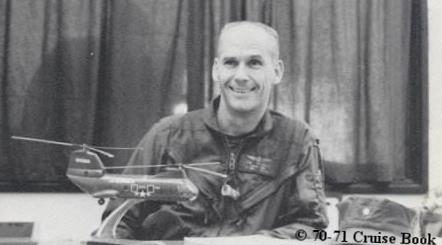

Model Marine

By Jim Brasher

This is a story about a young man I knew during the Great Depression and the days, months and years of World War II. This story should be told now because of the rapid decline in the number of living World War II veterans and others known as The Greatest Generation. We have Tom Brokaw to thank for that designation.

Henry Steadman grew into manhood while living with his family on Leverette Lane, a few miles south of the little farm community called Paynes, which is near the county site of Tallahatchie County - my own hometown, Charleston. To say he grew up in a poor farm family is not necessary; nearly everyone in that day and time fit that description.

But Henry was different in many ways: he stood tall and straight, with a serious look about him as though he knew where he was going in life; he was quiet and unassuming, but determined to make the most of every opportunity that came his way. Those qualities paid off handsomely in later life, as we will see when we get further into his career path.

On 1 June 1945, right out of high school at Paynes and Charleston, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps at the recruiting station in Jackson, Miss. and thus began 33 years of distinguished service for his country. In fact, as I pored through stacks of files on his military career, I came to the conclusion that this man is one notch from being a legend in his own time.

To anyone who has ever served in the Marine Corps, boot camp has a very special meaning. It is the time and place for rigorous training, which at times seems harsh, even tortuous. But it is for a purpose: changing a boy or girl into a Marine. Henry Steadman passed all the tests with flying colors, but there was a lot more to come. Let us now take a brief leave of absence from the military aspects of his story and let him be on his way out of Parris Island; that's not a bad feeling.

It was a random encounter at a local supermarket that brought Henry Steadman's life and career back into my consciousness after a lapse of over 60 years, during which time I had no knowledge of his whereabouts nor had I heard from anyone who knew him. Imagine my surprise when his sister, Juanita Steadman Murphy of Oxford, Miss., saw me and called my name there in the supermarket. That was a joyous reunion and one that posed many questions about her brother, who since my last contact with him had risen in rank from recruit at Parris Island to retired Col. Henry W. Steadman, USMC, a highly decorated Marine combat pilot and commander of a helicopter squadron in Vietnam. Before we get into the details of his military career, however, there is a lot of ground to cover, some of it incredible to say the least.

Back to Parris Island for a moment before the incredible starts, an unexpected event took place that got the undivided attention of the whole world: Japan surrendered and World War II was over. That is, the battles were over, the guns were silent and our troops were on their way home. Marine Henry W. Steadman, as quoted in Leatherneck Magazine, had this to say: "Japan surrendered, unconditionally, a week after I graduated, but I'm not vain enough to believe that news of my becoming a Marine had anything to do with the wonderful news of the day."

Another quote from Steadman is apropos here, because it turned out to be almost prophetic in the course of events to follow: "The Marine Corps was losing men by the thousands. World War II vets were returning home and being released from active duty. Rank initially came fast."

Had I been a successful Hollywood writer, producer or director in the film and TV industry, I would have jumped at the opportunity to portray Henry Steadman as the consummate Marine combat hero in the role of commander of helicopter units in Vietnam, but I would also tell the whole story of his life, from farm boy to retired colonel, U.S. Marine Corps. One reservation here: Henry would object to the use of the word "hero." The title of the proposed movie would likely be "Model Marine," because that's precisely what he became in his 33 years of exceptional service for his country.

Speaking of 'model Marine,' Steadman had this to say in an interview with Leatherneck: "I was lean, tall, and looked good in uniform." That was not an overstatement. I saw those stand-alone recruiting posters showing him in his dress blues, and it appeared he had been melted and poured into them.

We have now reached a transitional point in telling the story of Marine Henry W. Steadman. It has to do with the 'incredible' we mentioned earlier. Off in the distance I hear what sounds like the whistle of an approaching freight or passenger train. Now it comes into view. It is like no other railroad train; is it the Chattanooga Choo Choo? No. Could it be the old Seaboard Airline passenger train? No. Maybe it is the Orange Blossom Special? No, wrong again. It was called THE FREEDOM TRAIN. And thereby hangs the most incredible tale of all.

Sgt. Henry W. Steadman surely must have been in the right place at the right time for the next episode of his life story. It would have been the dream of a lifetime for any young Marine to be chosen from a group of over 200 to form a security detachment on board the Freedom Train. Only eight were selected from the group at Camp Lejeune, where Steadman was stationed at the time; the others chosen came from various units, and all of them were sent to Marine Barracks Washington to form the detachment. Their mission was both to guard and protect those priceless archives and documents, and to showcase them to the thousands of visitors who would be coming aboard the train.

As Sgt. Timothy C. Hodge reported in his “One Marine, Many Memories”: "more than a rolling museum, the Freedom Train was an educational and patriotic program that provided a vivid reminder of the greatness of America's heritage to a nation still recovering from economic depression and world war." It should be noted here that the idea for the Freedom Train was born and came to fruition in the mind of William Coblenz, assistant director of the Department of Justice's Public Information Division, who then got the support of his boss, Timothy A. McInery, who enlisted the participation of Attorney General Tom Clark, and through him got the "strongest endorsement" of a man we all knew very well: the President of the United States, Harry S. Truman.

As Sgt. Henry Steadman voiced his reaction to the whole concept of the Freedom Train, in his own words: "Being selected to be a part of the detachment for the Freedom Train was one of the best times of my career. It was a great honor to be one of only a few sergeants and corporals selected from across the Corps for this assignment." Money can't buy the kind of publicity and fame showered on Steadman and his fellow Marines aboard the Freedom Train as they traveled by rail over 33,000-plus miles across America - all 48 states, visiting some 300 cities and towns. Visitors came aboard by the thousands and were amazed to see and experience so much of America's heritage in such a historic setting.

One of the lesser known attributes of Henry Steadman, in both his personal life and his Marine Corps career, was his incessant desire to better himself, and those qualities drove him to seek more and more training and education wherever he happened to be at every stage in his career. Not long after the Freedom Train experience, he attended Memphis State College, and in 1970 earned his bachelor’s degree from George Washington University. Shortly after this he pursued and received his master’s degree from the University of Southern California.

Again, quoting Timothy C. Hodge, "Later he applied for and received a commission as an officer. He went on to become a decorated pilot ….” He earned two Silver Stars for heroism and two Legions of Merit; his first Legion of Merit with Combat “V” was awarded after his second of two Vietnam tours (1971) and he was awarded his second Legion of Merit at his retirement ceremony in 1978. Additionally, after 500 combat missions in Vietnam, Col. Steadman was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, two Vietnamese Crosses of Gallantry, 25 air medals and a Purple Heart.

It is not within the nature or scope of this story to sermonize about the merits and/or justification of the war in Vietnam; enough has already been said and written on that subject. But in the final analysis, it is the prerogative of the warrior to make the assessment of his or her risk factors each day of combat as they step aboard the aircraft and, under orders from their superiors, fly into enemy territory, hoping and fully expecting to live and fight another day. Every time Col. Steadman took a seat in one of his helicopters and prepared to do battle with the enemy, he put his life on the line. The point here is: the politics of war just don't seem to matter when life-and-death decisions are being made.

As he described in his own handwriting the 1959-1964 gap in the chronology of his service, he spoke of his first helicopter assignment; “it was flying the world's largest helicopter, the HR2S, which held the world's speed and altitude records." This turned out to be a forecast of his future, the harbinger of things to come, as he entered a new phase in his Marine Corps service - the war in Vietnam. As quoted from Leatherneck, “he flew 21 different Marine aircraft, commanded Aircraft Group 29 at New River N. C. and graduated from the Command and Staff College, and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. I began as a Marine recruit and administrator, just like so many other Marines. But I set goals and worked as best I could to achieve those goals ….”

At this juncture in the chronology of Col. Henry Steadman's service in Vietnam, it is time to select a few outstanding episodes in which he, as commander of the Purple Foxes, wrote an essential history of that war, as he was in the thick of the action from Day 1 of his involvement in it. To write a full disclosure of this entire engagement would approach the impossible due to both the intensity and the length of it. Most of the documentation supporting Col. Steadman's Vietnam experience as we are writing it came to my attention as a result of a vast amount of tedious research done by the colonel's niece, Dawn Murphy of Dallas, whose mother is Juanita Steadman Murphy, Col. Steadman's sister previously referred to. Anything more than a short version of Col. Steadman's life story would certainly require writing his biography.

Now, back to the war in Vietnam: Some further explanation of the Purple Foxes is in order here. In December 1964, Lt. Col. W. C. Watson assumed command of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 364. It was during his time as commander that the squadron became known as the Purple Foxes. In another change of command in September 1970, Lt. Col. Henry W. Steadman replaced Lt. Col. P.C. Scaglione as commanding officer. It was in this month, September 1970, that the squadron accomplished almost 1.500 hours of flight time - the record for the squadron's tour in Vietnam.

It was during the following month of October that HMM-364 engaged an unexpected but near-catastrophic event: the worst monsoon flooding in the Da Nang Valley in years. As reported by HMM-364, the Purple Foxes rescued some 1,500 victims of the flood and they also rescued about 400 civilians, disregarding completely IFR weather. The next day they flew 58.5 hours and rescued about 1,000 people, in spite of zero/zero weather conditions, without gunships. On 22 March 1971, the Purple Foxes HMM-364 was decommissioned, but not forever. HMM-364 was reactivated in September 1984, but that is another story for another day.

It would seem to an outsider that our troops fighting the war in Vietnam had to deal with a crisis every day, and that may well be true; however, some crises in that war were more threatening than others, as Marine Sgt. Mike Easton recalled in his letter to a fellow Marine detailing what happened at the crash site of chopper YK-22. It was an emergency situation calling for a backup unit from Marble Mountain, and the grounding of YK-22. This is where Lt. Col. Steadman came into the picture by reversing his decision on the backup chopper to rescue another team asking for reinforcement immediately.

But this rescue chopper had serious problems of its own and was about to go down. Lt. Col. Steadman told the co-pilot, "We are not going to make it." The helicopter crashed, rolled down the mountain and immediately burst into flames, resulting in serious injury to some of the crew, including several who were badly burned. As stated in his Silver Star citation, “By his courage, bold initiative, and unwavering devotion to duty in the face of great personal danger Lieutenant Colonel Steadman was instrumental in saving the lives of two of his fellow Marines ....”

Although the above is limited information regarding Col. Henry Steadman's distinguished military career, it is easy to understand his acceptance as a member of the notable Golden Eagles.

In conclusion, we are reminded of the many and varied honors bestowed on Col. Henry W. Steadman as reported in this “mini-biography.” His career in the U.S. Marine Corps has been phenomenal, to say the least. Anyone who proposes further honors for him has only to review the citations in support of the two Silver Stars and the Distinguished Flying Cross awarded for his bravery and dedication to duty in his long and honorable career. Col. Henry W. Steadman, USMC.

We Salute You!