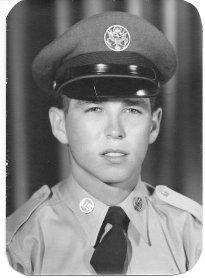

Four years as an Air Force air traffic controller during the Korean War was my introduction to the gender wars. Upon discharge in 1956 I returned home from Alaska unannounced. You know those heart-tugging TV scenes we see of loving wives and children greeting returning veterans? It wasn’t like that.

A babysitter let me in and hurriedly left. I kissed the two sleeping little ones, and waited until my wife and live-in boyfriend returned from carousing at a nearby VFW club (of all places). I had suspected something like that. When I heard the key in the door and opened it, the guy ran down the apartment stairs and wasn’t seen again, though others were. I called a cab, threw my wedding ring in a nearby swamp, paid the driver handsomely to get me a (after hours) bottle of whiskey and take me to a sleazy hotel in downtown St. Paul. I drank the bottle and don’t remember much after that. Thus began a decades-long nightmare.

With dreams and hopes for family and future shattered, my then wife’s continued preference for a non-marital lifestyle lead to a bitter divorce in l957 and subsequent custody fight, all the way to the state Supreme Court, which I lost of course, being male. I was shocked by the animosity directed at a male who dared buck the system. It was a bitter and shattering experience, especially for the children―who became brainwashed and alienated.

After discharge, I was hired by the Civil Aviation Agency, later the FAA, in various control towers, mostly in Minneapolis. I struggled with depression and alcoholic self-medication. The situation affected my work. On some days inbound aircraft would come in great waves, as depicted in the movie, Pushing Tin. After work some of us controllers might go across the street to the NCO Club (now long gone) for a few drinks to relieve tension. Three or four scotches usually did the trick. One night, still feeling effects of the previous night’s imbibing, I had a potentially catastrophic near miss (very near) in instrument weather conditions (quarter to half mile visibility) between a military jet and a fully loaded civilian airliner. I had cleared the military jet to land, forgetting about the airliner sitting out of sight on the runway awaiting takeoff. The jet broke out of the clouds just prior to touchdown and landed long, probably passing less than 200 feet over the airliner (This contrasts with several aircraft “saves” during my military and civilian careers). I still have occasional nightmares reliving that near miss. Now it could probably be called PTSD.

Fearful of a recurrence of the incident and pauperized by increases in my alimony/support obligation, I resigned from the FAA in 1966. I practically lived out of my car briefly, sometimes surviving on peanuts and water. I nearly became one of those homeless vets on the street―58,000 of them in the U.S. according to the September 2014 issue of the American Legion magazine.

I hired on for several years in Gulfport Mississippi as commercial pilot and flight instructor. A realization that the treatment of men in and after divorce is but part of a broader pattern of discrimination motivated me to work in the trenches of the early men’s rights movement and begin writing my book “Doyle’s War, Save the Males” (Amazon.com).

In addition to many accolades from the legitimate branch of the men’s rights movement, and happily remarried, I am now an honorary lifetime member of American Legion Post 225 in Forest Lake, Minnesota. One of the things veterans fought for is freedom. If freedom means anything, it means freedom of expression however politically incorrect. I sacrificed too much in defense of freedom to walk away from it now.