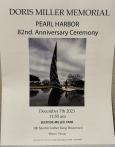

Photo: World War II veteran and grasshopper pilot Charles Rogers stands in front of his Piper Cub. Rogers’ plane had an image of a baby on it, in honor of his first child being born, a daughter, Clare.

During World War II, Charles Rogers, now 95, flew more than 100 missions, unarmed and without parachutes, through the front lines of battle in Europe. He received an air medal with two oakleaf clusters for his service.

As a grasshopper pilot, he steered a nimble Piper Cub to safety, despite facing off with Germans, along with their Messerschmitts and Long Toms. The grasshopper pilots brought an observer with them, who would examine the terrain and direct artillery fire.

"This was extremely effective," Robert Mitchell, curator at the Army Aviation Museum at Ft. Rucker, Ala., said. "It was so effective that a lot of times the enemy would stop shelling if they saw one of those airplanes."

This allowed the Americans to adjust and prevent artillery fire, he said.

"The First World War they had balloons, but this was a little unprotected Piper Cub. We were flying 800 feet above the German line. When the war was over, it was never going to be again. They went to helicopters. Now they don’t even use helicopters — they use drones. We were the only ones," Rogers said.

Each artillery battalion had two grasshopper aircraft and two pilots to operate them, Mitchell said. They flew in Europe, North Africa and the Pacific.

Before the war, Rogers had completed college in Rochester, N.Y., studying art. But when the Americans joined the war, Rogers enlisted, excited for what lay ahead. Rogers served over a year in the Fourth Armored Division. But they remained stateside.

"I was a happy-go-lucky young guy. When I was growing up I always admired the World War I pilots. I used to read those avidly - the books about the air battles in WWI," Rogers said. "A lot of young guys were trying to join the Air Corps just to get out of the Army because they weren't sending us over right away, and we were itching to get over. I saw a notice on the bulletin board that they wanted artillery officers to volunteer to learn to fly small planes."

The Piper Cubs would fly close to the ground and had to land and take off from small fields, and other difficult-to-maneuver-in areas. The lightweight planes were unarmed.

"Naturally the Germans tried to shoot us down. They did a damn good job, too. I was just lucky. That's how I lasted so long."

The high-risk job killed many and caused many others such mental distress they had to be hospitalized, Rogers said.

While we were up there, the Germans fired anything they could at us. They fired anti-aircraft fire, which was like little bursts of popcorn all around. They would fill the air with it," he said.

The German's Long Toms also loomed.

"When that shell burst around you they would make a lot of noise and burn red orange with dark black smoke and frighten us all over the place. Many times you could feel the artillery shells going past your plane, under and around it. You almost always came back with small fire shells or fragments of the big bursts that burst around you," Rogers said.

Then there were the Messerschmitts, which would sandwich the Piper Cubs.

"One would be high—you'd see him up there and he'd dive on you, but you knew there was another one because they always had one low. One upstairs and one downstairs. We would be close to the ground, and he would come in there and pick us off if we were not lucky enough. We had to get down and fly our airplanes close to the ground through big groups of woods and hide behind things so they didn't shoot us down."

Because of their position at the front line, the grasshoppers could also catch friendly fire.

"We were very susceptible to being shot down by our own artillery because we were flying right in front of it. One of my friends did get shot down with a 155 shell—that's a big one. It went right through his observer. He was also riddled. When he came down he was a nervous wreck and they had to send him back home. He couldn't fly anymore."

But fear and pride were secondary to the basic priority of maneuvering the plane out of harm's way.

"You're so busy doing your job, you don't think of those things. Usually your heart's going boom-boom-boom. You're dodging - I had to dodge with that little plane all the time.

Rogers' strategy was simple.

"I made damn sure that we didn't fly in a straight line in any direction," he said.

Luck was also on his side.

Once when Rogers and his observer, Kelly, were "well behind the front line," they spied a little village and what they believed was Patton’s division.

"They were having a hell of a battle there between the German and American tanks. Next thing I know, there was a stream of fiery red shells that were probably 50 caliber machine guns. They were coming up right close to my right wing—so close that I flipped the plane to my left and took a dive to get out of there," Rogers said.

Kelly "almost squeezed outside the plane trying to get away," he said. Somehow they made it back.

The sergeant, who regularly checked the planes upon arrival, asked if they knew they'd taken some artillery fire.

"I said, 'Yeah, I know. Kelly almost got it in the rear end.' I was laughing at poor Kelly. Sergeant says, 'No, there was one that just missed your left foot. It went on through the engine but it didn't hurt the engine, so you were lucky there.'"

Once, he hid from enemy fire behind a large black cloud of smoke from a German oil refinery that had been set ablaze. (A hometown friend, Don Vogt, saw him from the ground, where he was fighting.)

On one pitch-black night, he flew a plane through the Alps, and at one point he and his observer had to scrape ice off the wings with their fingernails. They returned safely to the surprise of the officers.

"By that time you could control that little plane like it was part of you," Rogers said.

On another trip through the Alps, and because of wind currents among other issues, the plane was headed straight for a small town "where the Germans were with their full forces," Rogers said. Able to turn around without even being shot at, Rogers returned his post.

"No bullets. And so when I got back, I said to the major, 'I got a lucky one.' He said, 'You were lucky. The war was over. . . . That's why you didn't get shot down.'"

Rogers and his outfit were shipped back to the States, where they were to train for flying the Piper Cubs in Japan. At New York Harbor, there was a giant celebration—actress Marlene Dietrich even danced on the pier, Rogers said.

"We got pure milk for the first time and donuts. Boy, that was good," he said.

The war in Japan ended before Rogers shipped out. After the war, he and his wife, Mary, grew their family, and he became a commercial artist. He immediately joined The American Legion in Geneva, N.Y., which boasted a nationally recognized Drum Corps.

His interest in sharing his story as a grasshopper pilot sprang from a dearth of resources about the Piper Cub fliers online. To this end, he’s been interviewed at the World War II Museum in Natick, Mass.