The graceful, tree-lined boulevards of Montevallo, Ala., are several thousand miles and a million painful memories from the scene of some of the most savage battles fought in the island-hopping campaigns of the Pacific during World War II. For an ever dwindling number of U.S. veterans of that war, those memories have been tucked away for years in dusty footlockers along with old letters, campaign medals and faded photographs. Each spring and fall, however, those poignant memories had a way of surfacing for Eugene Sledge, former Marine and retired professor of biology at the University of Montevallo. It was during the months of April and September that Sledge was drawn back to the time he and his comrades in the 1st Marine Division spent amidst the hellish realities of war on the islands of Peleliu and Okinawa.

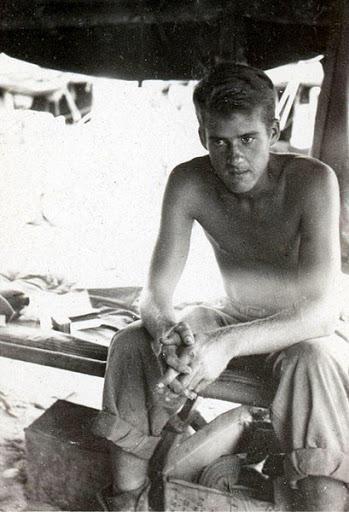

The 1st Marine Division, the “Old Breed” as it was known, was part of the 47,561-man III Amphibious Corps spearheading the invasion of Peleliu, a 2-mile by 6-mile coral rock in the Palau chain in the southwestern corner of the Pacific Ocean about 500 miles east of the Philippines. Operation Stalemate, the invasion of the Palaus, was designed to secure the eastern flank of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s assault on the Philippines and provide a base for air operations in that campaign. On the morning of 15 September 1944, Eugene Sledge was a 20-year-old private in K Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, crouching in an amphibious landing vehicle carrying him to his destiny on the smoke-shrouded beaches of an island whose name he had never heard. He later wrote, “Everything my life had been before and has been after pales in the light of that awesome moment . . .”

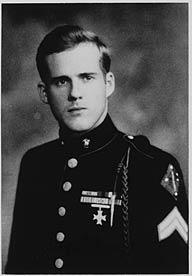

Sledge’s odyssey began while he was a student at Alabama’s Marion Military Institute in the fall of 1942. A Marine Corps recruiting sergeant, resplendent in his dress blues, visited the Marion campus, and Sledge made up his mind to earn the honored eagle, globe and anchor of the leathernecks. Like thousands of fresh-faced young men across the United States, his greatest fear was that the war would be over before he had a chance to do his part in the great crusade against the forces of tyranny.

After Marine Boot Camp in San Diego, Sledge and his youthful comrades underwent five months of combat training exercises on the Pacific islands of Pavuvu and Guadalcanal. Almost 85 percent of the men in his unit had not yet seen their 21st birthdays.

Following a furious naval and aerial bombardment that had begun a month earlier, three infantry regiments of the Old Breed were poised to storm the beaches of Peleliu. Their Marine Corps training had imbued the young warriors with the fire and vinegar necessary to keep a man alive in combat. The commander of the 1st Marine Division, Maj. Gen. William Rupertus, shared the confidence of his men. He told his commanders “....this is going to be a fast one. It’ll be over in three or four days – a fight like Tarawa. Rough but fast. Then we can go back to a rest area.”

The 13,000 Japanese troops defending Peleliu had different ideas. Col. Kunio Nakagawa was the Japanese commander responsible for the island’s defenses. He and his troops of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 14th Division fiercely held to the ancient Japanese military code of “bushido,” the established set of moral principles held by the Samurai warriors that dictated their way of life and honor until death. With no hope of being reinforced or resupplied, the entire garrison was committed to offering themselves as the ultimate sacrifice for their emperor and killing as many Marines as possible in the process.

Nakagawa utilized reinforced steel and concrete bunkers, virtually untouched by the aerial and naval bombardment, in conjunction with Peleliu’s natural system of over 500 caves, limestone ridges, jagged coral outcroppings, and debilitating 100-plus degree heat and suffocating humidity to make the Marines pay dearly for every foot of coral they won. It was into this setting, compared to two scorpions in a bottle, that the opposing forces met three-quarters of a century ago.

After all the planning by the admirals and generals 4,000 miles away at Pearl Harbor, all the aerial bombing from pilots 1,500 feet above the island, and the furious naval bombardment from sailors 1,000 yards offshore, it remained for Sledge and the foot soldiers, struggling under as much as 60 pounds of combat gear, to scramble across Peleliu’s exposed reef and come face-to-face with a determined enemy in some of the heaviest fighting of World War II in places such as Bloody Nose Ridge that made up the island’s Umurbrogol Pocket.

During the next 28 days of his life, Sledge recorded on slips of paper the events that would be forever burned into his memory. Memories of the incessant heat, burning thirst, and choking coral dust. Memories of the gallant doctors, corpsmen, and stretcher bearers - 303 of whom would find their final resting places in Peleliu’s military cemetery. Of chaplains intoning their prayers over dying men. Memories of friends who would forever remain teenagers and whose mothers would place gold stars in the windows of their homes. And of the “thousand-yard stares” on the faces of his friends who had survived, but had grown suddenly old after days of vicious fighting, omnipresent fear and sleepless nights filled with the terror known only to those who have experienced combat against a determined enemy. Sledge kept the papers tucked snugly away in a small New Testament that he carried with him through the war.

By the time the 1st Marine Division was relieved on 15 October by the troops of the Army’s 81st Division, the three regiments of the Old Breed had all but ceased to exist as combat units. Of the 9,000 troops that splashed ashore a month earlier, 1,252 had been killed and 5,274 were wounded. The mental and physical exhaustion of the survivors was so complete that many of the leathernecks were unable to climb the landing nets onto the Navy ships that took them off the island. The Army would lose another 3,278 men before the island was officially secured at 1100 hours on 27 November.

Almost 11,000 Japanese died defending Peleliu. Only 19 soldiers and sailors were among the 300 mostly Korean and Okinawan laborers taken prisoner. Colonel Nakagawa burned the ceremonial colors of his command and disemboweled himself on 25 November, 72 days after the invasion began and two days before the island was officially declared secured. The National Museum of the Marine Corps has listed Peleliu as, “the bitterest battle of the war for the Marines.”

Eugene Sledge was in good company in his first taste of combat. During the entire Pacific war, 19 members of the 1st Marine Division were awarded the Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest decoration for valor. Eight of those medals went to members of the Old Breed for their actions on Peleliu. For its role in the invasion, the 1st Marine Division was awarded its second Presidential Unit Citation (the Division has now garnered nine). In all, the division participated in four amphibious landings in the Pacific, a record unsurpassed by any Marine or Army unit.

After six months of refitting and reorganizing, the division was poised to enter the abyss again, this time on Okinawa, the largest island in the Ryuku Archipelago only 340 miles from the Japanese mainland. American commanders recognized Okinawa’s strategic importance as a fleet anchorage, troop staging area, and airfields in close proximity to the main Japanese islands. The Japanese knew the Americans would invade Okinawa, and were prepared to sacrifice their entire 100,000 man garrison of the Japanese 32nd Army to defend it.

As Easter Sunday 1945 dawned in the Pacific, Sledge and his comrades were again crouching in amphibious landing vehicles as part of the largest amphibious operation that took place in the Pacific war. They knew that the Japanese defenders, fighting this time on their own territory, would be possessed of a fanaticism unknown even on the other killing fields in the Pacific.

Sledge and his Marines were part of the 182,821-man American Tenth Army, which consisted of the Army’s 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions; the 1st, 2nd, and 6th Marine Divisions; and ships and aircraft of the U.S. Fifth Fleet.

Eighty-two days after the invasion began, the fighting on Okinawa finally ended. During that time, Sledge and his comrades lived amidst the death, mud, misery and heaviest concentration of artillery and mortar fire experienced by American troops anywhere in the Pacific. The battle came to be known as the “typhoon of steel” in light of the ferocity of the fighting that took place, the intensity of the Japanese kamikaze attacks on Allied naval vessels, and the sheer numbers of Allied ships and armored vehicles that assaulted the island.

Casualty figures were staggering. Of the estimated 12,520 American combat deaths and 38,000 to 55,000 wounded, more than 7,600 were members of the Old Breed. Nearly all of the 100,000 Japanese defenders died on the blood-soaked, 60-mile long island.

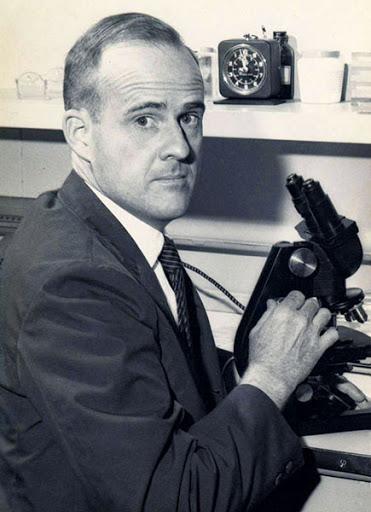

Sledge returned to his native Alabama after the war and enrolled as a student at Alabama Polytechnic Institute, which became Auburn University in 1960. After having dealt with death for two years, he decided on a career studying life. A Bachelor’s degree in biology in 1953 was followed by a Master’s degree two years later. In 1957, he entered the University of Florida where he was awarded his doctorate in biology in 1960. He worked as a research zoologist before opting for the small town atmosphere and a professor’s position at the University of Montevallo where he eventually retired in 1990.

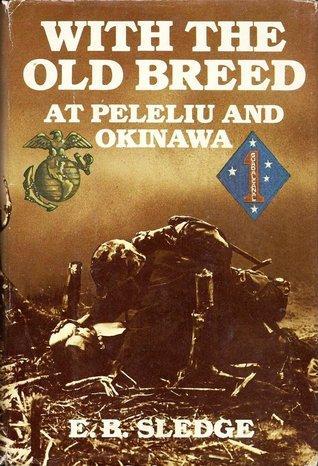

In 1981, Sledge published With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa, a compilation of his personal experiences during those two epic battles. The book has been heralded as one of the most compelling and graphic accounts of the terrible realities of war in the Pacific from the perspective of a front-line soldier. Paul Fussell, literary historian, author, university professor, and decorated World War II veteran with the 103rd Infantry Division, wrote what is perhaps the most powerful review of Sledge’s book. “With The Old Breed is one of the finest memoirs to emerge from any war,” Fussell wrote. Pretty impressive critique, especially from a man whose own book, The Great War and Modern Memory, was ranked Number 75 on Modern Library’s Board’s List of 100 Best Nonfiction Books of the Twentieth Century.

Sledge’s book is now part of the history, political science, and western civilization curricula at numerous colleges and universities around the country. It is also widely read by members of today’s Marine Corps going through their Boot Camp training.

Sledge has also appeared on several discussion panels on the war in the Pacific at the Marine base in Quantico, Virginia. In 1992, Sledge was featured in the documentary film Peleliu 1944: Horror in the Pacific. Ken Burns drew considerably from With The Old Breed for his 2007 World War II documentary The War. In 2010, Sledge’s book, along with Robert Leckie’s Helmet For My Pillow, would form the basis for the HBO series, The Pacific, where actor Joseph Mazzello played the part of Eugene Sledge writing notes in his pocket Bible.

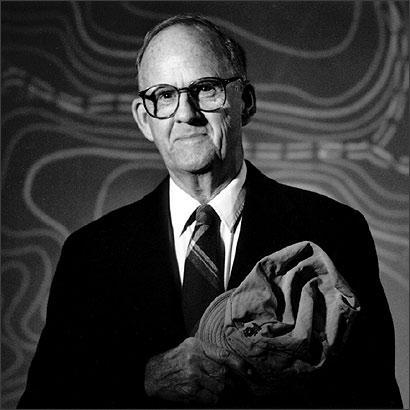

Sledge was invited to return to Peleliu in 1994 to take part in a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the battle, but he declined the offer. Even after a half-century, the memories were still too powerful.

On Sunday, 4 March 2001, the United States Marine Corps added another name to the honored list of their brothers who no longer answer the roll call of those who served during World War II. Eugene Sledge of Montevallo, Alabama, quietly succumbed to the enemy to which all old soldiers eventually surrender - time.

Those of us who knew Eugene Sledge continue to miss him. He always found time to sign one of his books or sit for an interview with this writer. We also swapped barracks stories about times long past. Our nation lost a true patriot.

The obscure islands in a far-flung corner of the vast Pacific were forever seared into the memory of Eugene Sledge and the men of the 1st Marine Division who established a place of honor for themselves in our history books. The inexorable march of time continues to dwindle their number, but it can never diminish their glory or the debt we owe them. True to the motto of the Marine Corps that he loved, Eugene Sledge remained “forever faithful” to the memory of his friends and to the proud brotherhood of which he will forever be a part.

Semper Fidelis.

Niki Sepsas is a freelance writer and international tour guide living in Birmingham, Ala. He can be reached at nsepsas@gmail.com or on his website nikiwrites.com.