I was enrolled in college in 1966, and the Vietnam War was really getting hot. My father was a 100 percent disabled World War II vet, having lost both his legs, so I qualified for benefits to go to school. From as far back as I can remember, I carried crutches, pushed wheelchairs and fetched whiskey and beer. I was born April 28, 1945; Mussolini was executed that day in Giulino and Hitler committed suicide on April 30th. My father shares a birthday with Hitler, and I share mine with Saddam Hussein. In those days newborns and mothers were kept in the hospitals for about two weeks. I came home in the VE Day parade in our Pennsylvania town. Dad had been out of the service for a year due to his health, so I was a pre-Baby Boomer, but for him and our family, the war was far from over. His legs were frozen, and over the next many years he first lost his toes, then his foot and then his left leg, the years after that his right toes, foot and leg. As a young child, I spent a lot of time at the Bay Pines VA Hospital feeding squirrels, pushing the wheelchair and witnessing all the human carnage the war wrought. I was not enthusiastic about going to war.

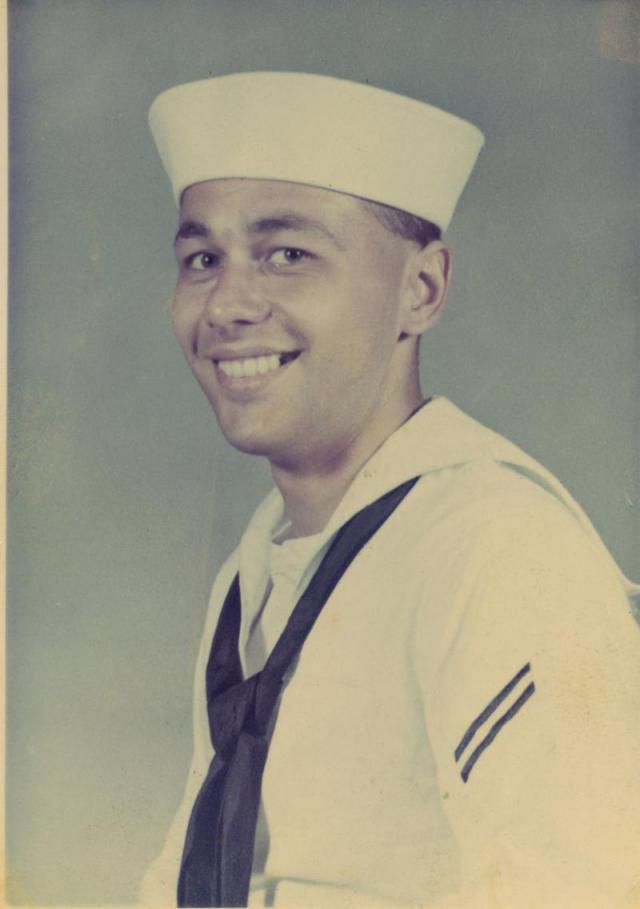

During the last semester at college I only needed a few hours to graduate to move on to a four-year college, so I carried a light load. A few weeks after the semester started I got my draft notice and my deferral was withdrawn. They weren't even going to let me graduate. I went to the Navy recruiter and signed up on the Junior College Program; this allowed me 120 days to complete my associate's degree and guaranteed me E-3 out of boot camp and the A school of my choice, providing I passed all the qualifier tests. I was majoring in geology and was most interested in photo intelligence.

I was sent to Great Lakes Naval Training Center. I got there when the place was in transition from old World War II or earlier barracks to new nice brick buildings. At first, we had to get all our hair chopped off, send all our clothes home and get issued new uniforms. Each night at the beginning was in these old buildings, now just a large open shell in various degrees of dismantling. We had no lockers, just bunks, and in the bathroom there were no stalls or doors between the commodes, oh, and only one roll of toilet paper at a time to share among 100 of us. For a kid that didn't even shower at the end of physical education classes, the exposure was very embarrassing.

After a few days, our Company 509 was marched over to new barracks, where we were each assigned a locker and a bunk near it. Our sea bag included a "Blue Book," the Navy's idea of a boot camp bible. We were issued a 1903 Bolt action and a .30-06 Springfield rifle. These were used in World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. We would spend many hours on the grinder drilling with it.

The company commander was a second class petty officer. He was short, seemed quite old and was quiet spoken. He apparently had been watching us, and soon chose the barracks master at arms, drill leader and perhaps an assortment of other jobs, but these two would be "in our face" more than most.

I am 5 foot 9 inches, weighed 135 pounds and was in incredible shape, having been running 3 to 5 miles per day and working out on the elementary school gym sets in the play yard, scuba diving and water skiing. There was nothing in boot camp that taxed my endurance. In fact, I gained 10 pounds from the inactivity.

Right after we got our lockers and "Blue Book," I took the initiative and read the thing. Where it described and diagrammed how you fold your clothes and place them in the locker, I did it. Then the company commander came to the quarterdeck (center of the barracks) and called a meeting. He went over basic rules, said to learn the 10 watch rules (which no one ever asked me one) and to fold our clothes and put them in our lockers.

"When you are through you can write letters home," he said.

Everyone started in folding, and I started in writing. He was walking around looking at the progress, and when he saw I was writing, he asked why I wasn't folding clothes. I told him I was done. He asked which locker. To me it was obvious—it was the one where everything was folded to spec and all the corners were lined up. He went over and grabbed the bottom item in each bin and yanked it out, dumping my entire locker on the floor. Then if that wasn't the happiest moment so far, he issued me a "happy hour." Happy hour is held daily in a hangar for the malcontents to do exercises with their 9.5-pound Springfields. There were a lot of guys in there. I figured if they meted out punishment for doing the right thing ahead of time, I won't be getting a raise for showing initiative and doing a good job. I will get the exercise I have been craving. But after doing deep knee bends, jumping jacks, twists, push-ups and holding my piece straight in front of me as long as I could, I actually felt like I got some exercise.

But the way I got railroaded I could become a malcontent. I was still sore about the way it was done. I guess some guys couldn't hack it; after the happy hour, we went to dinner and their stomachs just couldn't hold it. However, Navy chow was quite good and, for me, fattening. I gained 10 pounds in boot camp.

We were there for the cold winter. Peacoats got rolled and hung on the hooks on the back wall. But some of the guys got out their Navy-issued pocket knives and started throwing them at the coats, trying to stick the blades in them.

One day on the grinder, our sister company was drilling next to us. Both "flock leaders" turned their companies—one left, the other right. We went left; they went right. There was a clash of bodies and rifles. Of course, they instill in us a feeling of camaraderie, loyalty and pride in our company, and we competed for flags to carry before our company. Even though there were some punches thrown, nothing was to come of it.

Our barracks master at arms was one of us chosen to lead and keep the barracks and troops in line. Because he was repeatedly the bearer of bad tidings, some guys developed distaste for his methods. One night when he went to the showers, they threw him a blanket party. The group walked in, threw a blanket over him and beat the pulp out of him. The next day he had bruises and a black eye. I don't remember seeing anyone paying for that carnage either. He must have just slipped on a bar of soap. He did tone it down a few notches, though.

Soon it came to pass that each week they'd line us up for air gun shots in the arm and an occasional needle in the butt. The Bicillin shot stiffened some legs though, and some guys had trouble getting out of bed the next day. But it was deemed we were tough enough for the obstacle course. Our company commander led us out there for the experience. He meticulously described the course, "over this, through that, up this, down that, chin up here, push-ups there." It was all so mind boggling. At the end, he paused, looked at us and said, "Well, it's time for dinner. I don't know about you, but let's do that instead."

So off we went to dinner, and that was the last I saw of the course.

Remember the part about “I’d get the A school of my choice if I passed the right tests?

Well, we got tests—all kinds of tests.

I sincerely tried to do my best, but then there was one test that was just hopeless, communications. They'd play a record of dots and dashes, and then we'd mark the answer. The first few were training, so we understood what they wanted us to do. Our answer sheet was A, B, C, D and E columns and numbers down the side for each answer. They cut loose with the record, a brief training dot, dot, dash, and then it would rattle out a bunch of them and we had to choose an answer. I tried really hard on the first five or six, but I saw they advanced one letter to the right for every number down the page. What the heck? I'm not interested in communications, so I just Christmas treed the entire test with that trend. I was done shading in spaces long before the recorded test was over. Days later, the counselor kept trying to talk me into going into communications. I kept saying no.

"But you aced the test!" he said.

I had to tell him I just guessed the code.

Then there was an important test for me. I wanted to be a photo intelligence man. One of the requisites was you had to see 3-D, or stereo. I was directed to look through a binocular-looking device on short legs, straddling a sheet of paper filled with jumbled letters. As I looked through the lenses I was asked, "What do you see?"

Well, it jumped right out at me. It said: "I can see stereo."

This is right up there with Christmas tree communications.

The Navy is going to be no sweat. They do keep it simple. Much to my chagrin I didn't know how simple. When I got my orders after boot, I was not sent to my A school in Denver. I was sent to Saufley Field, Pensacola, Fla. I was not granted E-3 and I did not get my A school. To add insult to injury, the day I got there I was sent to the galley for four months. I just got thrown in with all the other dots and dashes. It took four months of begging and pleading to get them to send paperwork to Washington to get my situation straight. I finally got my rank, back pay and A school, but that's another whole can of worms. My wife bought me a 1903 Springfield for Christmas this year so I can relive my happy hours with a smile.

I am John Labie, PT 4. I made PT 5, but didn't have enough active time to accept it. I was delayed by paperwork SNAFUs. I finally finished college in geology, became a certified photogrammetrist (remote sensing), the trade I learned in A school and did work in that capacity for the state of Florida for 35 years.