Every Memorial Day white crosses decorate the front lawn of the historic Bleckley County courthouse in downtown Cochran, Georgia, each one representing the life of a fallen soldier.

Behind the courthouse, across Cherry Street beside Whipple Lane, stands a white frame house with a welcoming front porch. It is now a thriving business, but for many years it was the home of the Hendricks family. In this home Barney W. Hendricks Jr. was born in 1925, the only child of Barney W. Hendricks Sr. and his wife Margaret, a woman, I was to learn, who was quite remarkable.

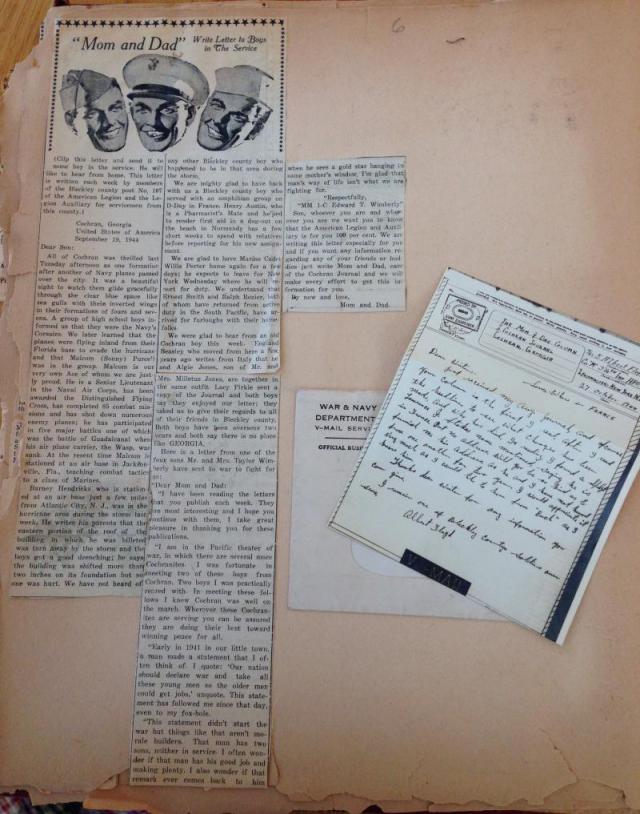

It was friend and native son Barney Jr. who suggested the idea of writing about his parents’ World War II-era column that ran in The Cochran Journal from August 1, 1944 to August 8, 1945. To pique my interest, he loaned me a crumbling scrapbook filled with yellowed newspaper clippings and original letters from soldiers.

At ninety years young, Barney possessed the quiet demeanor of a Southern gentleman. He remained tall and handsome with a head full of hair, recognizable in the photograph of himself as a young soldier in uniform.

With a ready smile he was quick to show me pictures of his family, pulling out pages copied from a local history book. He was also eager to share memories, telling about the time he rode in the back of a truck all the way to Washington, D.C. with the Boy Scouts, or the permanent head injury his father received in the First World War when a helmet, with a heavy pistol inside, fell off its nail on the wall of a wobbling boxcar onto his sleeping father.

He laughed, “I’ve got lots and lots of stories!”

Mostly, though, we talked about his mother and her unique idea for maintaining morale during wartime. Margaret Cook had come to Cochran in 1920 as the first home economics teacher of what would become Middle Georgia State University.

When she chose to marry, Margaret’s teaching career of only two years ended, the social mores of the day dictating that teachers could not be married. Later, having witnessed the devastation wrought by the Great Depression, she found a new career in 1937 as Director of the Welfare Department, a job she kept for thirty years.

The Welfare office was housed under the steps in the front corner of the same courthouse now decorated with flags and white crosses. There Mrs. Hendricks interviewed those seeking help, inquiring how many chickens they had? Was there a cow for milk? There were rules. Folks had to demonstrate self-sufficiency to qualify for the one or two dollars a week of public assistance.

Often, though, her day didn’t end with the five o’clock chime of the courthouse clock. Knowing they wouldn’t be turned away, the downtrodden would come up the alley in the middle of the night to knock on the outside wall of the sleeping house. “Can you help us?” they’d ask. “There’s been a death. We need a burial box.” or “My wife’s had a baby. Can you give us some baby clothes?” Margaret always did what she could, donating twenty-five cents a week from her own meager salary to help those less fortunate.

When the United States entered World War II, Margaret watched as her son and other local boys boarded the train, called into action and destined for the far corners of the earth. Barney himself joined the Army Air Corps, stationed in North Africa with the Air Transport Command.

She missed her son terribly, but with characteristic strength and resolve, Margaret was determined to make something positive of the situation. Barney’s father was a past Commander of the American Legion, and his mother served as an officer in the Women’s Auxiliary. According to The History of Bleckley and Pulaski Counties, Georgia (1808-1956):

“Servicemen at home on furlough were visited and when one of them expressed a need of mail from home, Barney and Margaret Hendricks began their Mom and Dad column in the local paper. These homey letters gave news that was culled from replies received from men stationed in all parts of the word. They were well received by the service men and home folks alike.”

Under the auspices of the Auxiliary, “Dear Mom and Dad” ran for fifty-five weeks, each column beginning with a suggestion to the Bleckley County citizens:

(Clip this letter and mail it to some boy in the service. He will like to hear from home. This letter is written each week by members of the Bleckley County Post 107 of the American Legion and Auxiliary solely for the service men from this county.)

Each one ended with a personal message to the soldiers:

Son, whoever you are and wherever you are we want you to know that the American Legion and Auxiliary are for you 100 percent. We are writing this letter especially for you and if there is anything you want to know about your friends or buddies just write “Mom and Dad”, care of the Cochran Journal, and we will make every effort to get this information for you. Bye now and love, MOM AND DAD

Barney’s parents carried out their labor of love incognito during the column’s first months, preferring to be known as simply “Mom and Dad”. Margaret is credited with writing and compiling the column, but she’d include comments like, “Dad says, ‘Keep ‘em rolling!’” or, when describing the celebrations at the war’s end, “Dad says folks are ‘hog wild’!”

She deliberately kept the tone upbeat with Dad’s colorful observations: “They are right on those German’s necks and are chasing them out and back to Germany like a martin chases a buzzard when it comes too close to his gourds.” or “That boy is so far back in the jungle they use hyenas for air raid sirens!”

There was friendly advice, “Son, you mustn’t feel too badly about the British Tommy’s not liking you so well.” Margaret compared the celebration of a young man home on furlough to “killing the fatted calf” and news of a soldier’s wedding was described as “sailing on the Sea of Matrimony!”

She shared sad news of each war casualty with, “One of the stars on the flag has turned to gold”, or “We regret to inform you…”

“Occasionally there was an error, blamed on “a little gremlin” or explained as “the Printer’s Imp got into our column and shuffled up the letters”.

The weekly column became a conduit of information gleaned from sources as varied as letters and phone calls, telegrams and Red Cross cables, even Morse Code signals blinking from passing ships. Some letters were printed verbatim, others were paraphrased, “We heard from Joe and he says…”

Information also came from parents and wives who shared their loved ones’ addresses and whereabouts. News arrived from Europe, Africa, India, and China, from the beaches of Normandy to the Hawaiian islands, from exotic spots like New Guinea, Panama, and Tunisia, or vaguely “Somewhere in the Pacific”.

Some letters were mailed directly to “Mom and Dad”, care of the newspaper. Many came via V-Mail, the letters copied and reduced to one-fourth their original size, sometimes blemished by a censor’s black marks. One guy joked about writing his mother a letter, “It was so interesting the censor kept most of it!”

A common theme in the soldiers’ writings was Home. “There’s no place like Georgia,” one wrote. “Looks like Georgia dirt.” and “The sun was as high as a Georgia pine.” “Good old Cochran”, “Pink speaks highly of Cochran and Bleckley County, always introduces himself as ‘the boy from that town I’ve been telling you about.’” “Been around a lot in the Atlantic and the Pacific but there’s nothing beats the old town.” “I’m just another Bleckley County boy.” “Thank God we have a home to return to in the good ole’ USA”.

The soldiers’ often praised the column, with words like “Thank you Mom and Dad”, “I read Mom and Dad before I read anything else.”, “The column is darn good.”, and “Nothing braces the morale of a soldier like a letter.”

One enclosed two dollars for his subscription, saying, “I’m still getting the paper, and I want to keep it coming, for each copy is just like a letter from home.” Another said he “even read the legal advertisements!” Still another said, “When I read, I feel like I’ve read the contents of several letters.” One described how he shared the papers with his buddies who then got down a map to locate Cochran.

Enlisted men wrote asking for cards and cigarettes and candy. One desired a pair of brogan shoes. They longed for ham and fried chicken with hot biscuits. One joked, “I am trying to find a blonde about five feet two inches tall…”

They told of eating caviar, snails, and grasshoppers. They spoke of jobs like signalman, radio operator, small arms instructor, loader, tank driver, machinist, and pharmacist. There was talk of foxholes and furloughs, unlikely reunions in places like Hawaii, and pastimes such as making jewelry from captured enemy equipment. They related tales of bombings and sand storms and life as a soldier. “It is remarkable how close disaster brings people together,” one wrote.

At last, with the end of the war in sight, the war-weary “Mom and Dad” column took a well-earned rest, concluding their final entry (rather naively, we now know) with, “Now that the U.S. has invented the atomic bomb, which will destroy everything well beyond hollering distance, it is hoped that the Japs will see fit to give up. Dad says that he hopes that the Americans won’t have to do a thing now but watch the flight of the atomics…”

The fighting boys, including, Barney Hendricks, Jr., returned home, part of what became known as The Greatest Generation, their service to their country often forgotten, or left in old scrapbooks.

Only a couple of weeks after our visit, Barney passed away. I regret that he wasn’t able to see this tribute to his parents’ newsy wartime column and to the soldiers who inspired it. Most of all, I’ll miss getting to hear more of his stories. Still, I’d like to think he’d be proud of this reminder of the days when there was no email, no Facebook or video chatting, a time when people hungered for news, any news, and longed for word from their loved ones.

As America faces continued conflicts at home and abroad, we’ll remember those who served and sacrificed with white crosses and flags and, yes, old letters. Thanks, Mom and Dad.

Within the old scrapbook, weekly "Dear Mom and Dad" columns were preserved alongside soldiers' letters.

"Dear Mom and Dad"

Cochran, GA

December 27, 2016

Submitted by:

Dawne W. Bryan