Three Feathers – Flagship of the 500th

By Joan Moore Liska, daughter of T.Sgt. Matthew J. Moore, gunner

Based on Oral and Written Contributions by

Capt. Edward Feathers , Air Commander, and

2nd Lt. Homer L. Bourland, pilot of Three

Feathers and other crew members

Flying off the deck of a carrier in the Pacific in February 1942, Doolittle’s Raiders led by Colonel Jimmy Doolittle had pulled off a risky, but monumentally daring bombing raid on Tokyo with a squadron of B-25’s. While the mission took the war to the enemy’s heartland and was a desperately needed morale boost for Americans in retaliation for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941, there was a significant short coming to Doolittle’s methods. The B-25s lacked the fuel to return from their raid. Many of Doolittle’s brave raiders did not make it to allied China and were forced to ditch behind enemy lines only to be killed or captured. It was recognized that this raid was not a battle strategy America could pursue. It would exhaust the supply of pilots, crew and planes before America could win the war. Clearly another method had to be forged to bring the war to the enemy’s door.

A TOP SECRET MISSION. In July 1943, General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Corp, was unfolding his plans to turn the tide on the Japanese. Boeing Aircraft Company was secretly developing long range bombers with the massive size and advance technology that would have the reach and capacity to attack Japan’s homeland.

The top-secret Wolfe Project, named for Brigadier General Kenneth B. Wolfe who would become the 500th Bomb Group’s first Commander on Saipan, was being unveiled by General Wolfe himself at Smoky Hill Army Air Field, Salina, Kansas to an elite group of 200 selected pilots.

“Gentlemen, you’ve been picked personally by General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Corp, because of your experience, prior training, education and being in the top 10% of your graduating class,” Lt. Homer Bourland recalls Wolfe’s welcoming speech.

The 200 pilots were introduced to the newest weapon system the Army Air Corp was developing, the B-29, the next generation of long range bombers. It would be BIG (141-foot wingspan, length nearly 100 feet and a tail that stood 3-stories tall). With a full load the B-29 would weigh 70 tons. The plane was so costly (approximately one Million Dollars each – a great deal of money in the 1940’s) and so sophisticated that the crew was assigned three pilots and every crew member would be dual rated to take another crew member’s job in the event of injury or incapacity.

NO B-29’S TO BE FOUND. The B-29’s were still on the production line in Seattle, WA when the first crews were gathered in Kansas. Classroom theory was taught by trainers rounded up from the only source then available, Pan American Airways flight crews who had China Clipper experience. Clipper crews were flying the lonely long distances over the Pacific Ocean before the outbreak of the war.

Lt. Bourland was assigned to combat training at Great Bend, Kansas after graduating from Smoky Hill. With no completed B-29’s to fly they practiced in B-17’s and B-26’s and finally on a YB-29. To simulate the expected trips over water to Japan, they flew one long range non-stop flight from Florida to Cuba.

By August, 1944, America had been fighting in the Pacific Theater nearly three years, primarily from aircraft carrier groups. America at last was ready to escalate the attacks against the Japanese with this new weapons system: Boeing’s most advanced long-range bomber, the B-29 Super Fortress.

THE CREW CHRISTENS THEIR B-29. Captain Edward Feathers was transferred to Kansas from Kearney, Nebraska. Feathers and his crew were assigned their brand-new B-29. Crew and plane became part of the 883rd Bomb Squadron, 500th Bomb Group. The number assigned to their plane was “Z SQUARE 49” and it was promptly dubbed “Three Feathers” after the Airplane Commander’s family of three with credit to the brand of the only bootleg whiskey available in Kansas.

Crew of “Three Feathers” that was formed in Kansas

Name and Rank Home Town Crew Position

Captain Edward Feathers Watauga, TN Airplane Commander

2nd Lt. Homer L. Bourland Vernon, TX Pilot and Flight Engineer

2nd Lt. Richard D. Metcalf Bombardier and Navigator

2nd Lt. Jack D. Alford Winfield, AL Navigator and Bombardier

2nd Lt. John E.D. Irving Montchanin, DE Flight Engineer

Cpl. William C. Taylor Willards, MD Radio Operator

Cpl. Ewald Schulz Detroit, MI Radar Operator

Sgt. Matthew J. Moore East Hartford, CT Central Fire Control and

Right-Side Gunner

Cpl. Ralph J. Darrow Rochester, NY Left-Side Gunner and

Electrician

Cpl. Elmer E. Burch Spartanburg, SC Ring Gunner and Assistant

Engineer

Pvt. Houston H. Powers Tail Gunner and Aircraft

Mechanic

S/Sgt. A.G. Swede Pearson Crew Chief (ground crew)

Combat Crew Replacements

Capt. Walter E. Landaker Kansas City, MO Squadron Bombardier and

Navigator (replaced Metcalf

who was transferred)

VanZandt (temporary replacement for Powers in Tail Gunner

July 1945 when Powers suffered a broken back in combat)

Cpl. Sammie M. Stultz Tail Gunner (replaced

VanZandt/Powers)

THE SOUTH PACIFIC. The newly assembled crew flew Three Feathers to Hamilton Field, San Francisco, CA “where we were briefed to fly to Hawaii and from there to Kwajalein Island and on to Saipan in the Mariana Islands which was to be our base for the balance of the war,” Bourland recounted.

MISSION TOKYO – BOMBS AWAY. Three Feathers first official combat mission was to the western outskirts of Tokyo on Thanksgiving Day, 1944 against the Nakajima Aircraft Engine Plant. 111 B-29s were on that raid; the first time that the northern island of Honshu and the Tokyo area had been bombed since the Doolittle raid of February 1942. That Thanksgiving Day mission was the first of 35 missions each member of the crew of Three Feathers would be required to fly.

Bourland recalled one of those early missions.

LEAD CREW – TARGET NAGOYA. “Our aircraft crew was ordered to lead the 73rd wing on the Mitsubishi Aircraft Manufacturing Plant at Nagoya, Japan. The weather was horrible all the way to the target forcing us to spread out the formation. We climbed above the overcast.”

Solid cloud cover plagued the flight until they broke out into sunshine over the coastline of Japan, thirty miles west of the planned coastal location. Three Feathers had lost its wingmen. Capt. Feathers turned his B-29 into an orbit to scout the area, but fuel shortage forced him to abandon efforts to reassemble the wing. Three Feathers flew east toward their assigned target to bomb the Mitsubishi Plant downwind.

“Just after ‘bombs away’ a B-29 approaching on our left suddenly opened fire on us with its front turret gun,” Bourland recalled. In the excitement of battle, the other B-29 had mistaken the oncoming Three Feathers as an enemy aircraft. The short burst of 50 caliber machine gunfire shot out the Airplane Commander’s [Captain Feathers’] controls, ruptured the nose wheel tire and shot out the propeller governor on the right inboard engine. The runaway part broke away and struck the just emptied bomb bay.

ON FIRE AND SPIRALING OUT OF CONTROL. Seriously damaged, Three Feathers veered into a screaming 30-degree dive. The pilot, Bourland, on the back-up controls fought the plane to keep it from spiraling into a fatal spin. The runaway engine was afire. The engine extinguisher could not snuff it. Feathers ordered his crew to prepare for bail out, and to await the signal to go. He would give the order if the fire reached the wing fuel tanks.

Then the burning inboard engine threw its propeller. As it spun loose, it collided with the outboard propeller and disabled the second engine on the right wing. Three Feathers was now operating on only two engines (both on the left wing). Amazingly, Bourland was able to pull the damaged B-29 out of its dive. He leveled out its wings as best as it could at 20,000 feet. For only the second time ever, a B-29 was proving that it could fly with two engines knocked out on one side of the aircraft.

About an hour into the emergency Three Feathers flew through a rain squall which turned into a blessing. The heavy tropical rain extinguished the engine fire. The crew was ordered to stand down from their emergency positions and return to their normal flight stations. To their relief, they would not be ditching or bailing out over the Pacific (at least as it looked for the moment).

SHORT ON FUEL AND A LONG WAY TO GO BACK TO SAIPAN. Once the aircraft was stable, the Flight Engineer informed the pilots that they had 6 hours and 30 minutes of fuel. Saipan was 6 hours and 15 minutes away. The margins were tight, but they could make it if the two-remaining overworked Wright 3350 engines hung in there. Three Feathers had already logged more than the recommended 400 hours maximum on each of her four engines. The pilots cut the RPM and manifold pressure back as low as possible. At 20,000 feet altitude and losing 200 feet per minute, they would be able to make it back to base, but only barely. The engineer informed them at that rate of descent they would be at 800 feet when they reached the cliffs of Saipan that edged the end of the runway. To add to the challenge, the navigation equipment was not working. Fortune was with them. Another B-29 in the area (piloted by Major Fitzgerald) took up station with them to serve as their point guard.

SAIPAN’S RUNWAY IN SIGHT. The fuel gauges were reading zero for the final 50 miles as they approached Saipan. The Air Commander’s controls had been knocked out and were thus useless. With his greater experience and the responsibility resting on his shoulders for plane and crew, Captain Feathers took over the right seat for the difficult landing ahead. With the beginning of the 10,000-foot runway looming just ahead and Three Feathers settling in at a 50-foot altitude, Captain Feathers leveled out the wings and shut down the remaining engines. What had been a noisy roar inside the huge B-29 became eerily silent leaving only the sound of the wind rushing by. The men held their breath as the 141-foot 3 story tall bomber glided across the rocky shoreline at the edge of the runway. Feathers ordered gear down. Seconds later Three Feathers made a perfect dead stick landing.

Major Fitzgerald in the escort B-29 landed right after them to join the celebration. Their remarkable flight had lasted 22 hours on a mission that normally took 15 hours. The next day when the fuel tanks were drained to work on the repairs it was measured that they indeed had only 15 minutes of fuel to spare.

FRIENDS LOST. Sadly, Major Fitzgerald and his crew were lost on a subsequent low-level bombing mission over Kobe, Japan.

HAZARDOUS DUTY. Radar Operator Ewald Shultz recalls that the missions had become so frightening that there were times crew members would step back off the ladder to vomit before climbing aboard to make the mission. CFO T.Sgt. Matthew Moore related the pure terror he endured when the night before a mission he dreamed that he would be assigned to fill-in at the tail gunner’s position and in his dream, he would be killed back there; the next day he received such an assignment. Despite the foreboding prescience of the dream, Moore did not refuse the mission, but he had to ask the crew member behind him to give him a boost into the plane. He just could not get his body to respond to swing up into the back. Fear and bravery were part of their job.

“Three Feathers I” flew 11 creditable missions before it was temporarily retired, to be refurbished and reassigned to another crew (its tail number would be changed for the new crew). The crew of Three Feathers I was given a new B-29 which was promptly named Three Feathers II; it also bore the Z-SQUARE-49 that was assigned to the crew.

DAMAGED AND BLOODIED THREE FEATHERS II LANDS AT IWO JIMA. Three Feathers II flew 18 missions until her last memorable mission over Kure, Japan on June 22, 1945. Colonel Dougherty, the 500th Group Commander, took over the right seat pilot’s position in Three Feathers II to lead the 73rd Wing in a maximum raid. Flak from the Japanese battleship Haruna knocked out Three Feathers left two engines, blasting a huge hole in the largest of the fuel tanks. Dangerous fumes flooded the crew aft compartment. In the forward cabin, the bombardier, Capt. Landaker, was soaked in blood up to his waist. The flak had pierced his boots, sealing him to the floor boards. Despite his agonizing wounds, Landaker flashed a relieved grin to the pilots when he found his groin intact.

With an injured crewman aboard and insufficient fuel to return to base, the badly damaged Three Feathers headed for another dead stick landing, this time gliding onto the runway of the recently liberated Iwo Jima. The island of Iwo Jima was roughly half the distance it would have taken to make Saipan. Three Feathers II was scrapped there for parts. The crew jumped a ride back to Saipan.

FEATHERS CREW TO THE RESCUE. Rated “war weary” by the flight surgeon who wanted the crew grounded, General Curtis Lemay had other ideas. Convinced that the war was nearly over, he ordered the experienced Three Feathers crew to train newer crews. Assigned a temporary B-29 replacement (Z-45), they were to fly “Superdumbo rescue missions” from Iwo Jima.

These missions were technically not combat missions yet these were some of the most dangerous missions flown. One such mission was flown August 3-4, 1945.

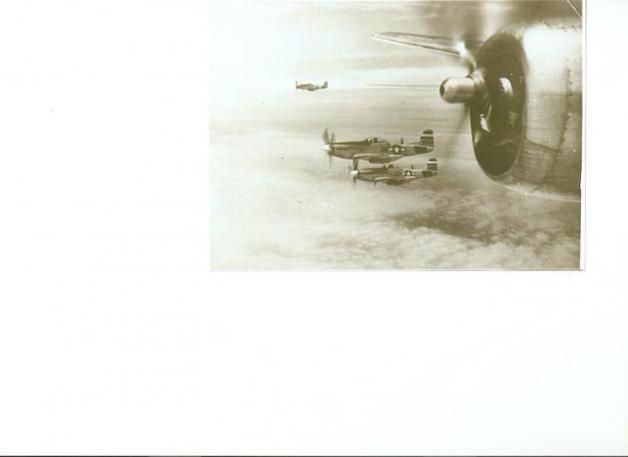

Feathers crew in Z-45 led the flight which was to pick up and escort the entire complement of the P-51 Fighter Wing on a “target of opportunity” mission against Tokyo. 50 miles out, south of Tokyo Bay, the P-51’s split off to head for their targets. Radio Operator Taylor established contact with a waiting submarine and began her protective orbit overhead of the action. The P-51’s had already engaged the enemy.

Very quickly the Three Feathers crew received an IFF Signal and a voice call of MAYDAY. A P-51 had crashed. Z-45 turned her heading toward the signal emanating from Tokyo Bay. Dropping to low altitude, they located the fighter pilot in the water, only his Mae West keeping him afloat.

“As we passed over him I had the bombardier throw out a survival kit. We saw him swim over to retrieve it,” related Bourland.

Japanese speedboats were closing in on the downed pilot, however. Seeing the danger, a second Dumbo, a modified B-17 equipped with a droppable boat, buzzed in to jettison the boat for the downed pilot to motor out to a waiting submarine.

Now flying at only 50 feet above Tokyo Bay, Z-45 weighed its options of climbing out or heading for the mouth of Tokyo Bay. It was risky as there would be no turning the super fortress at that low level. As they flew on toward the mouth of the bay, Capt. Feathers recalls “all hell broke loose as mortars and artillery began exploding all around us from both sides of the entrance to the Bay”. They had missed that a large enemy battleship was backed in a jetty right by the bay entrance. Somehow, the huge Z-45 managed to run the gauntlet and cleared the bay entrance unscathed.

Another MAYDAY call drew them to the other side of Chosi Peninsula. Just off the beach a P-51 pilot was in trouble. Still at low altitude, Z-45 flew right over a Japanese destroyer. No shots were exchanged, but Feathers knew that their position would be broadcast. He ordered another rescue kit to be tossed to the downed pilot (including flares and a rubber boat) before turning seaward. They flew out 30 miles, waited and returned to check on the P-51 pilot on 30-minute intervals.

“He had secured the boat, crawled into it and was getting along pretty well considering the circumstances,” according to Bourland’s assessment. “He waved in exultation as we passed over him giving us the impression that he was O.K.”

The nearest available submarine was 6 hours away, but coming on full speed on the surface. Z-45 was requested to remain on station.

“We advised the Sub Commander we were in spitting distance from Tokyo Metropolitan Area and that intelligence reports claimed there were 500 or more Japanese fighters in this area,” Bourland recounted.

With marginal fuel they agreed to orbit the area. On the next circuit they found the P-51 pilot under attack from “four Jap fighters busily strafing his position for all they were worth. We figured that was the end of him.”

Though they could not take on the fighters, they remained on station hoping for the best. The rescue sub arrived in the darkness. As sub and Z-45 closed in on the last sighting of the P-51 pilot “flares erupted like the 4th of July. It was our fighter begging somebody to help him.”

The Super Dumbo had stayed on station as long as her fuel permitted. She turned for base. Military secrecy dropped a curtain around that rescue but Bourland learned much later the first P-51 pilot survived an attack of 9 Japanese fighters thanks to a B-17 that shot down all 9. The American sub took him aboard shortly before he reached the mouth of the Bay and all escaped unscathed. Such was the happy ending to a hair-raising episode in the final days of World War II.

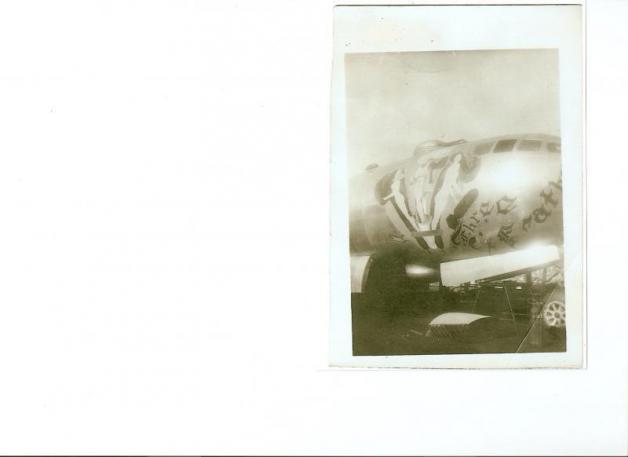

The crew received their third B-29 that was christened Three Feathers III and continued to fly combat missions until war’s end with this shiny new bird. On July 16, 1945, the 500th Bomb Group selected this plane for a special ceremony. Three Feathers III was dedicated as a "living memorial" to the 4th Marines.

CFO T.Sgt. Moore wrote to his wife and daughter, “We just came back from the dedication ceremonies of our ship. General O’Donnell, boss of our wing, made a speech. He said 2000 planes have used Iwo [Jima] up to date. That will give you an idea of why the ceremony was held. Plenty of pictures were taken and maybe we’ll get to see some of them.” That letter and the pictures are still in the Moore family archives.

The crew of Three Feathers (minus Powers who was absent) posed proudly in front of the newly unveiled nose art in tribute to the 4th Marines for their heroic efforts in liberating the Pacific islands of Iwo Jima, Tinian, Saipan and Roi-Namur and commemorating 2000 B-29s flying off Iwo Jima. It was particularly meaningful to this crew who had been able to use the newly won base at Iwo Jima for their emergency landing there.

WAR’S END

T. Sgt. Moore wrote home again (as he did nearly every day) on August 5th, 1945 that he had flown the last of the required 35 missions. “We flew 30 out of 48 hours again and that’s rough. Last view of Japan was appropriately that of [Mount] Fuji silhouetted against the setting sun.”

A beautiful photo of Three Feathers (Z square 49) leading a bombing mission past Mt. Fuji memorializes this plane and all of the B-29s that served in the Pacific in WWII. The photo is on a plaque recognizing Three Feathers and her crew at March Air Museum in Riverside California. The plaque was provided by the Moore family.

The next day, on the 6th of August another B-29, the Enola Gay, dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. The sun was indeed setting on the Empire of Japan. Three days later Bockscar, another B-29 Super Fortress flying from Tinian, delivered the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan. On that day, the 9th of August, 1945, the Japanese unconditionally surrendered to the Allied Armies. The formal surrender documents would be signed aboard the USS Missouri with an armada of B-29’s passing overhead.

At the end of the war, Three Feathers III was renamed Flagship 500 (in honor of the 500th Bomb Group). Gen. Lemay flew her back to the U.S. mainland in a long-distance attempt to make a Washington DC landing. The attempt came up short as Flagship 500 landed in Chicago [not bad for a WWII era bomber]. Three Feathers III’s last flight was in 1988 to Riverside, CA where she now resides in honorable retirement at March Field Air Museum, once a WWII air base. She is being restored to her former WWII condition.

*** In memory of the crew of Three Feathers and all of the B-29 crews of WWII and with gratitude to their service to our nation. ***

B-29s take the war to Japan's door

December 29, 2017

About the author:

Joan Moore Liska is the daughter of a Three Feathers crewmember, T.Sgt Matthew J. Moore (Chief Flight Control officer and right blister gunner). Letters that Matty wrote to his bride back home formed the backbone of this factual tale of one crew that served her country well.