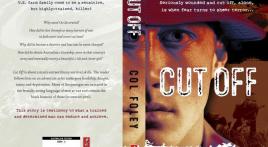

Colonel Elmer J. Wallace

Courtesy of USD Photograph Collection,

Archives and Special Collections, University Libraries,

University of South Dakota

“I may not write to you again with the sound of guns all about, and the most continuous whistle, whine and crack of shell… I do not like them, and I do not like the results I see from them, but not for years of life would I have missed being here and seeing this stupendous world effort, and being an active part of it.” – Col. Elmer J. Wallace, October 28, 1918.

Elmer J. Wallace grew up in a pioneer family in Elk Point, South Dakota. His father Norris, who was a Civil War veteran and held a teaching license, became the first instructor in the first public school in the Dakota Territory, which was “a fourteen by twenty log building with a dirt floor.” Norris later served as the county superintendent. In 1871, Norris married Annie M. Hays, who was 20 years younger. The next year, on July 1, 1872, Elmer Wallace was born in Vermillion, South Dakota.

Wallace spent his boyhood years in Elk Point before attending the University of South Dakota in the fall of 1893. In addition to studying academic courses, Wallace and all other male students were required to perform sufficient military drills during their first two years. Theoretical instructions were given at drills, which became a pre-requisite for the military courses in junior years for gentlemen. As a young man, Wallace was concerned about politics. In the fall of 1896, during a heated Presidential election between William Bryan and William McKinley, Wallace traveled home to Elk Point to cast his vote for Bryan. To Wallace’s dismay, McKinley was revealed the winner of a very close race. Ironically, years later, while serving in the military, Wallace personally attended President McKinley’s funeral.

In June 1897, Wallace completed his undergraduate studies and received his bachelor’s degree in Literary. In the summer of 1898, he earned his master’s degree in Literary. Soon after graduation, on July 27, Wallace was united in the holy bonds of wedlock to Adelaide Electa Beede. On August 4, Wallace entered the U.S. Army with the rank of Second Lieutenant.

Military Career

When Wallace entered the military, the U.S. was engaged in the Spanish American War (April – August 1898). However, he was not sent to war immediately. Instead, he was assigned to the First Artillery Band in the Coast Artillery Corps and was stationed at Fort Moultrie, Sullivan’s Island, in Charleston, South Carolina.

Wallace’s military career prepared him to become one of the nation’s experts in coast artillery defense. Depending on the military’s needs, Wallace was assigned to different coastal forts. He was stationed at Fort Moultrie for three years before he was promoted to First Lieutenant. From May 1901 to May 1910, Wallace was stationed at Fort McHenry (Massachusetts), Fort Monroe (Virginia), Fort Hancock (New Jersey), Fort Preble (Maine), Fort Warren (Massachusetts), and Fort Totten (New York). During his early years in the military, Wallace mainly performed duties or received military training. After he was promoted to Captain in 1903, his major assignments involved commanding companies and training army officers.

From May 1910 to October 1911, Wallace and two other captains were “assigned as assistants to the chiefs of their respective departments or corps for the Western Division with station at Honolulu,” and Wallace was “in charge of fire-control installation.”

Coming back from Hawaii, Wallace was first stationed at Fort Wood (New York). For the most part of that year, Wallace was on detached services as an assistant to the Chief Signal Officer, Eastern Division, making the annual inspection of Signal Corps equipment in the Artillery Districts in the Department of the Gulf. Afterward, Wallace was transferred to Fort H. G. Wright (New York), then to Fort Constitution (New Hampshire), continuing his duties as company commander.

The year 1917 was an important year for Wallace. After 14 years as a Captain, Wallace was promoted to Major in the Coast Artillery Corps. As his rank went up, Wallace assumed more important functions. In July 1917, he was “detailed as a member of the examining board at Fort Monroe, Va.” In the same month, Wallace was appointed to be a member of a board of officers, who met in Fort Monroe, Virginia, “to investigate and report upon antiaircraft fire-control system.”

In Wallace’s day, aerial warfare was in its infancy, and Wallace was a pioneer in the antiaircraft field. In his 32-page research article “Anti-Aircraft Weapons,” Wallace discussed in detail how to shoot captive balloons, dirigibles, and airplanes in battle. According to Wallace, there were mainly two ways to attack aircraft – “1. The attack of aircraft by aircraft. 2. The attack from the earth.” The article focused on gunfire as the primary method used in both cases and discussed how to mount guns on airplanes as well as on the ground in order to shoot at different types of targets with different types of projectiles. His article also examined the problem of gunnery – “The possible speed of aircraft is so great, and the target presented by an airplane is so small, that the problem of hitting one in flight is exceedingly difficult.” Wallace then went into detail to discuss the fire direction, grouping of guns, fire control, and fire control for guns in groups. Wallace used abundant technical terms, numbers, and graphics, which reflected his preciseness and profound knowledge on coast artillery defense.

When the U.S. joined World War I in April 1917, Wallace longed for an opportunity to be deployed to Europe. However, since he was one of the most efficient officers in the U.S. Army and that his experience “made him especially valuable in training officers and men for services,” the War Department did not want to send him overseas and risk him being killed on the battlefield. Due to his persistence, months later, his request was finally granted. Before he was sent to France, on January 12, 1918, Wallace was appointed to Colonel in the Coast Artillery. Commanding the 60th regiment field artillery, Colonel Wallace sailed for France in April 1918.

Falling on the Field of Honor

Immediately upon arriving in France, Colonel Wallace led his regiment into action, and they had the first taste of actual fighting. They “took part in some of the most important engagements of the latter part of the war, being in action in the famous St. Mihiel drive, and later in the decisive battle in the Argonne forest.” Seeing the cruelty of war and the destruction brought by the war, Colonel Wallace longed for a quick end of the war and peace for the world. In a letter home, Colonel Wallace told his wife:

"France Oct. 28

My Darling Girl,

I love you love you all and hope that we may be together again before a very great time.

Our wireless has just taken a copy of the Austrian note replying to Wilson’s last note, and apparently acceding to all his terms. Apparently Austria has quit. If so, it is more than the beginning of the end. By the time this reaches you, you will know all about it. I hope for a very early peace, and I think that a few more days of hard fighting may bring it. It is possible that I may not write to you again with the sound of guns all about, and the most continuous whistle, whine and crack of shell. I hope this may be the case. I do not like them, and I do not like the results I see from them, but not for years of life would I have missed being here and seeing this stupendous world effort, and being an active part of it.

We just had a gas alarm and I wrote a few lines while wearing it. I would not write this if I did not feel quite sure that when you get this the suspense would be over.

…

Good night – my darling girls. I love you love you love you!

Always Your Boy,

Elmer,

E. J. Wallace

Col. C.A.C."

The day after writing this letter, Colonel Wallace was severely wounded and immediately rushed to the hospital. Unfortunately, he remained unconscious for seven days and died on November 5, 1918.

Back at home, Mrs. Wallace did not know anything about Colonel Wallace’s death. Life was the same as usual. On November 10, Mrs. Wallace received her husband’s very last letter. Two weeks later, on Tuesday, November 26, 1918, Mrs. Wallace received a brief telegram from the War Department, which simply stated, “Deeply regret to inform you that it is officially reported that Colonel Elmer Jay Wallace Coast Artillery Corps died November fifth from wounds received in action.”

Telegram from the War Department to Mrs. Wallace

Courtesy of Jeff Kirby (Col. Wallace’s grandson).

The details of Colonel Wallace’s death came in a personal letter from Colonel L. R. Burgess of the Coast Artillery Corps to Mrs. Wallace. It included:

"Your husband was assigned to duty with my regiment and was placed in charge of the operative section. We moved forward to a valley surrounded by hills, and beautifully wooded, where we lived in two shacks built of tarred paper and birch poles. All went well until one night about 11:15 a hostile shell struck the corner of his shack and exploded, wounding him severely. We hurried him to the hospital where he remained unconscious for seven days. He died on Nov. 5, and was buried at Souilly, which is south of and near Verdun, on Nov. 6."

In August 1919, Mrs. Wallace received a letter, with heading “American Red Cross, General Hospital No. 2, Fort McHenry, Baltimore, MD,” from Lieutenant Maurice O. Woodrow, who was in the same room with Colonel Wallace the night of the tragedy. In the letter, Lieutenant Woodrow described:

"We were in a little summer house with rustic trimmings, just made of board nailed together. Although I came at night I have little conception of what it really looked like only it was a little “set-to.” house, rather shed.

Suddenly I was awakened by a feeling of fire in my limbs & unexplainable I remember instinctly [sic] of seeing the flash of the exploding shell although I had been asleep. I tried to move my legs but it was impossible but feeling around I found a man who had been blown or rolled over my legs & it was Col. Wallace.

I spoke to him & as he answered I realized that Col. Wallace was out of his head."

Lieutenant Woodrow also drew a diagram of the room in which they stayed that night, showing what had happened:

Diagram drawn by Lieut. Woodrow.

Courtesy of Jeff Kirby (Col. Wallace’s grandson).

Colonel Wallace’s death was a great loss for the nation, as he was one of the few high-ranking army officers and the only colonel of Coast Artillery to be killed in WWI. His death also left his family in deep sorrow. Mrs. Wallace loved her husband dearly. Three years after Colonel Wallace’s death, in the summer of 1921, Mrs. Wallace traveled to France to retrieve her husband’s remains, which were reinterred at the Bluff View Cemetery in Vermillion, South Dakota.

Legacy of Colonel Wallace

Colonel Wallace died on a foreign land, but his fellow countrymen did not forget him. The University of South Dakota commemorated him in different ways. In the fall of 1925, a new rifle company, the Wallace Rifles, was established on campus. In 1930, a tree was planted on campus in his memory.

In addition, after Colonel Wallace’s death, one battery, two military camps, and three American Legion posts were named in his honor: Battery Elmer J. Wallace (1919-1948) in California; Camp Wallace (1919-1971) in James City County, Virginia; Camp Wallace (1941-1944) in Galveston County, Texas; American Legion Col. Elmer J. Wallace Post No. 7 (1919-1940) in Fort Kamehameha, Honolulu, Hawaii; American Legion Col. Elmer J. Wallace Post No. 17 (1919-1924) in Fort Monroe, Virginia; and American Legion Wallace Post No. 1 (1919-present) in Vermillion, South Dakota.

References

“Alumni and Former Students.” South Dakota Alumni Quarterly XIV, no. 4 (1919).

Army Navy Air Force Register and Defense. Published on July 28, 1917.

“Coast Artillery Corps.” In Congressional Record, Volume LIII. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1916.

“Col. Wallace Remains Arrive.” The Plain Talk (Vermillion, SD), Jul. 28, 1921.

Collins, Edward. “A History of Union County, South Dakota, to 1880.” US GenWebs. Accessed on November 12, 2015. http://files.usgwarchives.net/sd/union/history/collins1937.txt.

“District of Hawaii and Artillery District of Honolulu.” In War Department Annual Reports, 1911. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912.

Quasquicentennial, Elk Point, South Dakota, 1859-1984. Elk Point, SD. Elk Point, SD: Elk Graphics, 1984.

“Report of the Department of Hawaii.” War Department Annual Report, 1912. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913.

“Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1806-1916 [database online], August 1902.” National Archives and Records Administration. Microfilm Serial: M617. Microfilm Roll: 797. Accessed on June 2, 2016.

“Shell Wound Caused Death.” The Plain Talk (Vermillion, SD), Dec. 5, 1918.

“The President’s Order Creating Military Department of Hawaii.” Hawaiian Star (Honolulu, HI), Oct. 17, 1911.

The University of South Dakota Catalogue: For the Year 1893-4. Vermillion, SD: The Dakota Republican, 1894.

The Washington Post (Washington, D.C.), Jul. 22, 1917.

“Two Army Colonels in Casualty Lists.” New York Times (Manhattan, NY), Dec. 4, 1918.

Wallace, Elmer J. “Anti-Aircraft Weapon.” Journal of the United States Artillery 47, (1917): 297-329.

“Wallace Rifles To Be Organized.” Evening Huronite (Huron, South Dakota), May 21, 1924.

“War Mothers To Dedicate Tree.” Evening Huronite (Huron, South Dakota), Aug. 13, 1930.