She was coming home and would know the place for the first time. This daughter of a Cold Warrior was born in the base hospital just a few blocks away. And while she had no memory of it, she was told that her parents and two older brothers had been happy together here. This is the last place any of them saw her father alive. But she couldn’t remember. She was only 6 months old when it happened. Shamaine Plezcko of Huston had been trying to find her way back here ever since.

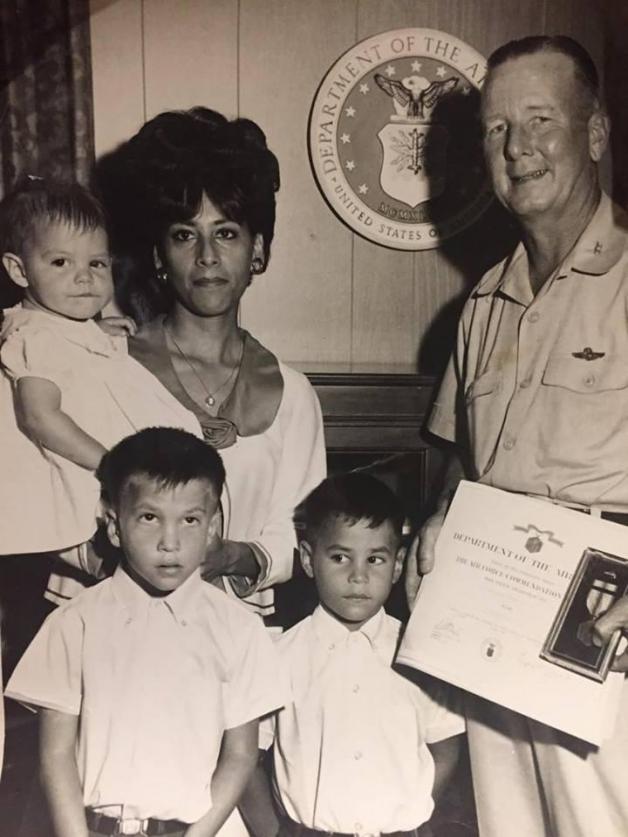

Air Force Capt. Manuel “Rocky” Cervantes was killed during an alert drill on 8 December 1964. He had lived only 29 years when his mother received an American flag in the mail along with an impersonal letter of condolences from Col. Paul K. Carlton, the commander of the 305th Bomb Wing at Bunker Hill Air Force Base in Indiana. Rocky’s wife had been told that her husband’s death resulted from an unfortunate training accident. Some of the less informed blamed Rocky for his own demise. The Indianapolis Star lauded him as a Cold War hero, having sacrificed his life in the interest of our nation’s peace, no less a casualty than if he had been shot on the battlefield.

And that was that. Virginia Cervantes moved her young family back to Texas. Shamaine would know her dad only through family stories and a few black and white photos. She spent 36 years wondering about the man who had rubbed his wife’s feet while she was pregnant, who possessed a sharp wit, an easy smile and a rich sense of humor. The man who could never comfort her after a bad dream, attend her school functions or walk her down the aisle at her wedding. And then they found his airplane.

Half a century and less than a mile from where Shamaine was standing on a warm Indiana day last spring, her father had breakfast in the mostly underground alert facility at Bunker Hill AFB. He wouldn’t know that a snowstorm had almost shut the base down until he went outside with his pilot, Capt. Leary Johnson, and his defense system operator, Capt. Roger Hall to conduct their daily preflight checks on 60-1116. The fully cocked supersonic bomber was parked nearby, ready for an emergency engine start and loaded with five nuclear weapons.

With the blowing snow limiting visibility on the runway, a KC-135 declared an inflight emergency and asked for permission to land on the base. Bunker Hill was a Strategic Air Command (SAC) installation and home to half the supersonic nuclear strike fleet, the B-58 Hustler. Command ordinarily discouraged intruders for security reasons but this pilot said he was in trouble. He wasn’t.

This kind of subterfuge was fairly common during a SAC Operational Readiness Inspection (ORI). The inspection team would come up with some way to sneak onto a base and then wreak havoc for a week while inspectors tested every squadron under wartime conditions. Just minutes after landing the SAC inspector general was escorted to the command post where he presented Col. Carlton with an execution order for a simulated emergency war plan mission.

Timing was critical. A third of Bunker Hill’s bombers and tankers were cocked on full alert. But before they could retaliate against a Soviet first strike the aircraft would have to escape the base ahead of an attack. Planners estimated that the defense early warning system might give the aircrews 15 minutes' notice. The clock started ticking the moment Col. Carlton received his orders.

When the klaxons went off that Tuesday morning Rocky ran for his airplane. Like a veteran fireman he was used to it. Rocky had been a SAC “crewdog” for nine years. He excelled as a B-47 bombardier-navigator while assigned to the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri before being reassigned to an exclusive Hustler crew with the 305th Bomb Wing at Bunker Hill in January 1962.

But what Rocky or anybody else never got used to was the exhilaration that came from being part of a B-58 crew. It was elite and often dangerous duty. During the eight year operational life of the Hustler at Bunker Hill and later Grissom Air Force Base, 17 airmen were killed in accidents involving 11 bombers. Two of Rocky’s very good friends, Maj. William Berry and Capt. William Bergdoll, burned to death a year earlier after they crashed during landing. As they left the base hospital after the accident Rocky promised Capt. Jack Strank that he would never die that way.

Alert crews were regularly scrambled under simulated wartime conditions to make sure they could launch in the required 15 minutes. But as the crews strapped into their aircraft that morning they had no way of knowing if this was just another drill or a real nuclear war. In Rocky’s bomber Johnson and Hall started the engines while he began decoding the emergency action message. The crew lowered their overhead hatches as the crew chiefs pushed the boarding stairs clear. Johnson released his brakes and began rolling toward the runway. Their bomber would be at the end of a line of aircraft launching eight seconds apart.

Johnson would later testify that he “saw a flash and the airplane lurched to the left”. Then Hall looked out his small window over the left wing and saw flames. The whole wing was on fire and Johnson ordered his crew to abandon the aircraft. Three overhead hatches blew off simultaneously.

Johnson climbed out of the cockpit and over the windshield. The heat was intense and flames licked at his clothing as he crawled across the nose of his aircraft and then jumped down into the snow. Hall likewise climbed out on top of the burning fuselage and ran across the right wing before diving into a snowdrift. Rescuers rolled him in the snow to put out his burning clothes and although not seriously burned he dislocated his shoulder in the fall.

Rocky had nowhere to go. Witnesses saw him rise briefly, like he was standing up in his seat to look outside. What he saw might have resembled the gates of hell. The Hustler was loaded with 14,000 gallons of military grade jet fuel and most of it was burning around the airplane. His position was forward of the wing so he had nowhere to run. Rocky disappeared back inside. Seconds later the rocket propelled ejection capsule fired into the gray December sky, climbed until it disappeared in the falling snow and then fell back onto the concrete taxiway, the parachute fluttering ineffectively in its trail.

The ejection or escape pod had been developed to protect a Hustler crew that had to get out of their 1,400 mile-per-hour airplane at 40,000 feet, where the temperature is 55 below and there’s no oxygen. When activated the pod would fold the crewman inside and then slam shut to seal out the dangerous environment outside the airplane. It was very effective at high speeds and high altitude but completely unsafe for a runway ejection because the parachute would not have time to open.

Col. Carlton reported the accident to SAC Headquarters as a “Broken Arrow”, code for an accident or incident involving nuclear weapons. Firefighters battled the flames for hours and two airmen were treated for injuries sustained during rescue operations. For the next 40 years former airmen would blame serious cancers on radiation exposure from the accident.

Dense, black smoke and flashing red lights were visible from U.S. Highway 31 and before the fire was out local media began to make inquiries. Initial releases reported a training accident that left a crewman dead. Base officials confirmed that the accident involved one of Bunker Hill’s nuclear strike bombers, but claimed the airplane was unarmed and there was no danger to the public. A news conference was scheduled for the next day.

Engineers, weapons technicians and firefighters worked to secure the accident site on a short strip of taxiway connecting the alert pads to the main runway. While the wreckage smoked and popped, the nuclear weapons were carried to a nearby ditch and buried in sand. All five bombs were transferred to disposal facilities in Tennessee and Texas 16 days later.

Just as promised there was a news conference at the base hospital the next day. Reporters were reassured that the accident was contained and there was no danger of radiation. After a briefing reporters asked questions of Johnson and Hall. Both men looked pretty good in their dress blue uniforms, despite Hall’s arm sling and everything they had been through the day before. A media photographer was even permitted to photograph the wreckage.

President Lyndon Johnson asked Defense Secretary Robert McNamara about the incident during his daily briefing on 9 December. McNamara confirmed the death of a crewman and assured the president that while the nuclear weapons had been destroyed there was no danger of radiation. He blamed the fire on a collapsed landing gear that split a fuel tank open.

Gen. Everett Holstrom led the investigation and later reported, “the high explosives in all five weapons detonated…The aircraft and weapons wreckage burned for two hours.” During recovery operations the next day, “the secondary of one of the (nuclear weapons) burst into flames. It was extinguished but then it happened again. The next day, when this secondary was moved it ignited again and was buried in sand.” He further reported that on 8 December Dr. Henry Briggs and Hal Stocks from the Indiana Board of Health had been summoned and were at the scene of the accident until 2000 hrs. But when a 1996 Senate inquiry tried to confirm the health department’s roll both men denied ever getting on the base. They both said instead that they drove six hours through the ice and snowstorm to reach Bunker Hill Air Force Base, only to be turned away at the gate.

Except for a young woman’s journey to discover her father and a lonely stand of trees along the south side of the runway, the whole thing would have been forgotten. The base was renamed in honor of Hoosier astronaut Gus Grissom and the remaining Hustler fleet was sold for scrap. A year before victory was declared in the long Cold War, somebody in the office of then-Indiana Sen. Richard Lugar recalled Rocky’s accident and arranged for another Air Force investigation. Not only was the ditch along the taxiway still showing traces of radiation, so was an area of woods south of the runway. Adjoining fields were used in crop production but the woods remained untouched. About 10 feet inside the tree line was a chain link fence and rusted signs designating the section as a controlled area. Nobody was allowed inside without the base commander’s permission.

Three more years passed and Grissom AFB downsized, opening up a substantial portion of former Air Force real estate for economic development. But like every other military base there were a number of environmental concerns, not the least of which were the two radioactive sites. The Indiana Department of Environmental Management worked closely with Air Force officials to remediate both locations.

Workers had just removed the trees in the woods and started digging when the crane began to uncover aircraft parts. First a section of landing gear, then an engine, then part of an ejection capsule. Before the excavation was completed three weeks later a team of historic aircraft experts had to be called in from Wright-Patterson AFB to identify the collection of parts. They confirmed that the exhumed aircraft was a B-58, serial number 60-1116, Rocky’s bomber. Exactly what happened that cold December morning in 1964 still remains a mystery. While anybody associated with the B-58 program will readily admit that the spindly nose gear was the airplane's Achilles heel, it’s unlikely to have collapsed in taxi. It may however have snapped if the airplane collided with the piles of frozen snow that had accumulated alongside the taxiway.

The most popular theory and the one supported by several eyewitnesses is that the accident was the result of jet blast and an icy runway. The pilots were all in a big hurry to get airborne and had lined up for what SAC called a minimum interval take off (MITO) launch. Since the Hustlers had to deliver their devastating cargo all the way to the Soviet Union they carried a tremendous reserve of fuel. Each bomber lugged a bulbous fuel tank mounted along the aircraft centerline and just below their primary nuclear weapon. This mission pod hung very close to the ground.

When the airplane in line ahead of Rocky’s bomber throttled up to enter the runway, the jet blast pushed his airplane backwards on the ice. The crew was busy and Johnson was most likely standing on his brakes. Nobody noticed they were sliding until either a runway light ruptured the mission pod or the aircraft was moving so fast that the nose gear struck a chunk of ice and snapped. Either scenario could have caused the mission pod to rupture and spray 4,100 gallons of jet fuel into the hot exhaust.

But in 2016 the whys and how’s didn’t matter much to Shamaine. She recognized that her dad was doing a dangerous job and that he understood and accepted the risks. Now she would have to try and understand as well. It was her quest to appreciate and a daughter’s unquenchable love for her father that brought her back to where it all started.

On Armed Forces Day weekend, just a few weeks before Father’s Day Shamaine and her husband Rick visited the Grissom Air Museum outside what used to be the Main Gate. Rocky’s only daughter received a warm and heartfelt welcome in the Museum’s Hall of Honor. While tears streaked the cheeks of faces in the crowd, Shamaine graciously thanked a room full of visitors for helping preserve her Dad’s legacy. Before she was permitted a rare close inspection of the Museum’s Hustler Shamaine met with Lt.Col. Jack Strank (Ret.) who had been on alert with Rocky and was one of the last people to see him alive.

Perhaps because of the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death, the necessary level of Cold War secrecy and misinformation surrounding the incident, or the discovery of his wrecked bomber almost four decades after the accident, Rocky has come to epitomize the sacrifices of every Bunker Hill and Grissom airman who stood on the forward wall of our Nation’s peace. While they were always cocked and prepared for war, peace was their profession.

A requiem for Rocky

Grissom Air Force Base, IN

December 6, 2016

Submitted by:

Tom Kelley